Monday, November 28, 2011

But It Will Kill Trees....

Saturday, April 23, 2011

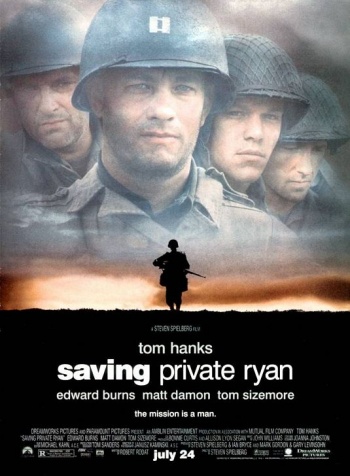

War is Hell

For the first opening half hour or so of Steven Spielberg's 1998 film Saving Private Ryan, you, the viewer, are subjected to a horrifying scene of utter chaos and carnage as American soldiers attempt to storm the beaches at Normandy on the morning of June 6, 1944. This opening scene has been called one of the most realistic depictions of war in cinema.

That may be but the truth is, even that doesn't quite come close. Typically in Hollywood when a guy gets shot you see a firecracker-like pop-eruption on his chest, then a bloodstain. The actor twitches violently with each shot, falling dramatically. We have come to equate Hollywood 'realism' with blood; the more blood, the more realistic the depiction. The reality of the violence a gunshot visits upon a human body is far worse, however, and far more random. There are all sorts of variables involved -- the caliber, some technical aspects of the bullet and powder, the gun itself, the distance between the shooter and the victim, clothing, trajectory, etc. etc. etc. -- but in the end, a bullet is really just a merciless little axe hacking away at its victim, arriving by a fancy delivery mechanism.

All of this might just be interesting trivia except for the internet, which is very literally an information superhighway that allows communication in ways unheard before the late 20th century. With the recent events unfolding in the Middle East, the internet has allowed people on the streets to take pictures of state violence and transmit them around the globe, proving that the dictators in Syria, Iran and Libya are lying as they deny their forces have attacked unarmed crowds. In particular, I receive through a group in Syria daily pictures of the violence inflicted on protesters by their own government. These pictures often show horrific images of corpses, of human bodies mangled in ways that Hollywood will never show (and shouldn't). There is a political point behind showing these pictures, because these people are suffering under tyranny and these pictures make the naked evil of that tyranny apparent to all the world. Still, they are also a sober reminder that the violence shown in Hollywood films, even in their most sensational moments, falls far short of the reality and to some extent that de-sensitizes us to the depth of suffering experienced both in war -- be it World War II or the Civil War or the Punic Wars -- and in unstable countries ruled by tyrants. It is also a reminder of what we have asked many of our veterans to experience, so that we do not have to. War is a part of the human condition, and as long as there are tyrants there will be war, but we should be more circumspect about when and how we wage war for as General William Sheridan noted after the Civil War, war is indeed hell.

Wednesday, April 13, 2011

Even the Brooklyn Bridge has its History...

Try to imagine the most startling news story you could think of, say, something like "Elvis discovered alive, and in bed with Jackie O, also still alive, while clutching stunning evidence of Loch Ness Monster and the Kennedy Assassination!" That's pretty good, actually. I wonder if the National Enquirer is hiring? I can do better than "Bat Boy". Anyway, it seems I have some competition in this department as news services the world over hummed with this amazing story this week: "Filmmaker claims to have found nails that hung Jesus". Notice they didn't even have to supply the "!"; you did that all by yourself as you read that.

So the story goes that a very controversial film maker and amateur archaeologist, Simcha Jacobovici, claims he's found, well, the nails used to crucify Jesus. Now, there's an entire story behind this and I'm not going to get into it. If you're going to pursue it, I would strongly suggest reading the opinions of some real archaeologists such as Bibleplaces.blog or A Hot Cup of Joe to see what the real experts have to say. However, there is a secondary, underlying story about this, one that transcends shysters and snake oil salesmen trying to gain riches and fame from the gullible, and that is the world of relics in Christianity, particularly Catholicism. The first thing that usually comes to mind are the many infamous medieval forgeries that produced enough pieces of the original crucifixion cross to fill a forest, and enough thorns from the crown of thorns to fill many gardens' worth of rose bushes, but these are really just the outer peripheral edges of an entire world of physical relics which Christians once -- and some still today -- use as totem-like bridges to important people and events from the history of Christianity. In this sense, Jacobovici's claim is less important to a historian as far as whether he's right -- whether they really are the nails that tormented Jesus Christ -- than that someone would take notice of his claims and try to verify them. In other words, these nails, whether they are what Jacobovici claims or not, represent a much larger Christian history and that makes these nails interesting to historians, that some today -- whether they believe Jacobovici or not -- take the topic seriously.

Tuesday, November 2, 2010

Halloween is Gone....or is it?

A friend of mine who owned a restaurant in Germany in the 1990s told me that she once asked her staff to wear costumes for Halloween, but as guests showed up, they asked in bewilderment why the staff were wearing funny costumes. Halloween is -- or at least was -- a very American holiday, but in many ways that's not really true. It has been spreading to Europe for some years now, so that only a few years after my friend's failed Halloween experiment, German children were donning ghastly costumes and declaring "Trick oder Treat" to candy-laden homeowners. It is by now a firmly-established tradition across much of Europe. Of course, it already existed in Europe before the importation of the American version.

In Central Europe, until very recently it was a more solemn religious holiday observed by families on what to Americans is Halloween night, but to Christians elsewhere is All Saints Day Eve. November 1 is All Saints Day on the Christian calendar, and so on the even before -- i.e., October 31 -- Christians in Central Europe go to their local cemetery at dusk and place colorful candles on the graves of their loved ones, and sit as a family and tell stories about those passed on, or just pray quietly. Because it's usually fairly cold at this time of year after dark this ritual doesn't last too long, but it is a beautiful sight to see the sea of candle lights dancing in the evening darkness. (Note the picture above from St. Michael the Archangel Church in Silesia, southwestern Poland.)

But of course, this Christian holiday has deep roots in Europe, roots far older than Christianity, roots more akin to the more pagan themes common in the American Halloween holiday. Pagan agricultural societies in pre-Christian Europe held huge parties in the autumn, end-of-harvest celebrations (like the Bavarian Oktoberfest) both to celebrate the end of a lot of hard work all summer long, but as well as a final send-off to the good weather, and recognizing in the process that a long, hard and potentially deadly winter lay ahead. For us today, winter is just a nuisance but in pre-modern societies, winters were a long period when all the food came from the previous summer's harvest, and if it went bad or if it ran out, then people simply died of starvation. Also, having lots of people huddled together in close quarters with minimal fresh air for months did wonders for diseases. This is why peoples threw a party in early spring -- like Mardi Gras -- as a sort of "Holy crap, we made it!" party, but it also shows you why people associated death with winter and fall. Add in the visual cues of the scenery seemingly dying in the fall and winter (only to be reborn next spring), and you have clear signs of death everywhere in the autumn, and so it was on everyone's mind. People began to believe that the autumn was a time when death entered the world, and the dead could interact with the living -- prompting lots of rituals and superstitions about how one should deal with them. Thus were born both Halloween and the Christian All Saints Day. Many of the particular trappings of the American Halloween such as jack-o-lanterns have been traced to pre-Christian Celtic practices, but the truth is that the essence of Halloween permeated nearly all of Europe.

Happy Halloween, folks.

Sunday, July 18, 2010

When does history matter?

We are, in 2010, slowly coming up on the 100th anniversary of one of the worst conflicts in human history, World War I, which raged from 1914 to 1918. This war invokes images of guys with huge handlebar mustaches wearing colorful, peacock uniforms marching stiffly on jerky old film reels. The war is over-shadowed by World War II in popular memory for a number of reasons, not least of which is the fact that World War II ended only 65 years ago, compared to World War I's 92 years ago. But World War II has other advantages on the popularity front as well: its battles were decisive, and its end clearer and beyond doubt. Both are sliding precariously out of living memory, but with the gamut of scholarly works and popular culture based on the Second World War, the danger is much greater for World War I.

Is World War I worth remembering? Iwo Jima, Midway, Stalingrad, Normandy; these battles are a part of the West's popular vocabulary today but who has heard of the three battles of Ypres, or the Marne, the Brusilov Offensive, or Gallipoli? And yet, these battles changed the world just as much as their Second World War successors. Wars are not sporting events and do not need cheerleaders, but it's a question of what is lost if World War I ever completely recedes from the popular memory.

World War I is the marker between the 19th century world and the modern world, where Victorian optimism about progress gave way to 20th century jaded cynicism, where stodgy old aristocratic feudal political structures made way for aggressive, energetic dictatorships bent on state-worship -- and mass murder. It was the war where the plane, tank and submarine would first be put to terrible use. Pre-war causes like workers' rights, women's suffrage and anti-colonialism, seen before 1914 as the goals of small bands of vocal extremists, became integral parts of the post-1918 world. Millions of men (and women!) around the world were mobilized for war or work, torn from their ancestral homes -- many of whom hadn't traveled but a few miles beyond their place of birth their entire lives until this point -- and met new peoples, new technologies, and new ways of doing things, and brought them home. One consequence of this mass mixing of peoples from all over the world was the 1918-1919 mass influenza epidemic, which killed millions more people than the war itself had. (It was exactly this epidemic world leaders were thinking about when they reacted so strongly to the 2009 H1N1 flu epidemic.) Another consequence was the birth of popular (mass) culture -- the French and Germans alike were astounded by American films and the jazz played by black musicians in the U.S. army in their off-time, while American and Canadian soldiers brought home memories of exotic foods from the lands they served in to small-town communities less impacted by immigration, giving birth to traditions such as American pizza and spaghetti. The mauling the war inflicted on the global economy forced governments everywhere to consider for the first time the necessity of government management of at least some aspects of national economies, though to what extent exactly is still a very contentious political issue today.

So does World War I matter to us today, some nine decades after the trenches emptied? If we have any interest in truly understanding modern political debates about aid to Africa, government regulation of the economy, or popular culture in general, then yes indeed, it would be of great value for us to look back and try to understand the events of almost a century ago that gave birth to many of these issues.

Tuesday, June 22, 2010

An Example of Perspective

I am tired of fighting. Our chiefs are killed. Looking Glass is dead. Toohulhulsote is dead. The old men are all dead. It is the young men who say yes or no. He who led the young men is dead. It is cold and we have no blankets. The little children are freezing to death. My people, some of them, have run away to the hills and have no blankets, no food. No one knows where they are--perhaps freezing to death. I want to have time to look for my children and see how many I can find. Maybe I shall find them among the dead. Hear me, my chiefs. I am tired. My heart is sick and sad. From where the sun now stands, I will fight no more forever.

- Chief Joseph of the Nez Percé, 1877

Today's mindless rant is born of technology, or more precisely, the failure of technology. In essence, I am using my little soapbox here to reply to someone else's blog because their "Leave a Comment" function isn't working. It's not their fault, but sound off I must, or otherwise possibly suffer a stroke. This is in reference to Dr. Mike Milton's 2008 blog -- hey, I'm just catching up now! -- about Norman Davies: "Norman Davies and the Appalling Problem of a Failure to Stand" (September 2, 2008; www.mikemilton.org). Now, I'll admit to being a Norman Davies fan but my point isn't to defend a man who doesn't need defending. No, I have other issues to grab my pitchfork over. First, take a moment and read Dr. Milton's entry. Go ahead; I'll wait.

I tripped across this entry by mistake while I was searching for something else. My reaction is not anger, just a sense that something fundamental is being missed. Whenever I read the quote above by Chief Joseph of the Nez Percé, my heart breaks. It is a quote saturated with sadness, weariness, exhaustion, but more importantly, defeat. This kind of experience is unknown to most Americans. Yes, the Confederacy lost the Civil War, and the Vietnam War ended in failure, but the Civil War was almost 150 years ago, and while the Vietnam experience was bitter for many Americans, it was ultimately something that happened over there -- somewhere else. Chief Joseph isn't just humiliated in having lost, he was speaking those words as a subjugated man whose destiny (and whose people's destiny) was forever more in someone else's hands -- his enemies' hands, to be specific. The Nez Percé's homes, their way of life, their beliefs; all were crushed and taken away by this defeat. It wasn't even just foreign occupation, it was exile, expulsion and virtual imprisonment in reservations, forever more at the mercy of their enemies' good will.

In his review of Davies' book The Isles, a History -- a history of Professor Davies' native British Isles -- Dr. Milton is upset at the book's seeming lack of British patriotism, and what he sees in both Dr. Davies and other similar Welsh experiences Dr. Milton had during a sojourn in Wales as a sort of Welsh tendency towards Balkanization, a centrifugal tendency among some peoples of Britain which fails to recognize just how good the British peoples have it in the United Kingdom, and how important unified national identities are. I'm not going to take issue with the last two statements, but I feel the need to explore the world a bit from the Welsh point of view for Dr. Milton's benefit.

I'll start by mentioning that I am neither English nor Welsh by ancestry. However, coming from a background in Eastern Europe, I have some insight into the kind of cultural forces that drive a people to behave as Dr. Milton witnessed in Wales, forces born of historic defeat and subjugation. The Scots were partners in creating the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, through a long process that began with the Scottish Stuarts holding both the Scottish and English crowns in the 17th century -- that part didn't end so well -- and ended ultimately in the Act of Union of 1707 by which Scotland and England united to form, well, the United Kingdom. This was a voluntary act by both countries which entailed debate in both their parliaments, and ultimately came down to a vote in both. For all the blustering of modern Scottish nationalism, the leaders of early 18th century Scotland chose to join with England.

Wales is a bit different. The Welsh are the descendants of the ancient Celtic Britons who fled first the Roman, and then later the Anglo-Saxon-Danish invasions of the British Isles. It is no mistake that Wales is a mountainous region; the ancestors of the Welsh literally fled to the hills. Turns out that wasn't enough, however; From before even Alfred the Great united Anglo-Saxon England in A.D. 845, the Anglo-Saxons and their English progeny constantly invaded Wales, and over several centuries' time, colonized its few towns. The Welsh survived as a culture by retreating further and further into the mountain wilderness, until there was nowhere left to retreat. Wales has spent its entire history ruled by Englishmen, often quite brutally. The last time a Welshman ruled Welsh territory, English was not yet a language, existing still as an Anglo-Saxon-Danish peasant language incomprehensible to even later Middle English-speakers like Shakespeare. Only in the 20th century has Welsh culture finally been able to openly be expressed, and Welshmen been able to take the first feeble steps in limited self-government since the 14th century, thanks to the Plaid Cymru revival movement. This is not so much a sob story as an opportunity to point out that Wales was decidedly not a voluntary party to the creation to the Act of Union in 1707. Wales existed only as a legal entity, whose title belonged exclusively to the British crown. The Welsh people were inconsequential to the British political unit called 'Wales'. The British 'Wales' effectively existed in London, not Swansea or Cardiff.

Now, the 20th century Wales that Norman Davies grew up in is a very different place and the massacres and humiliations of previous centuries are a thing of the past, but a culture that spends centuries under subjugation cannot so easily forget the past. Can Dr. Milton imagine what it's like to belong to a culture which has suffered foreign occupation and often brutal subjugation so long that most of your people forget their own language, adopting instead the language of the occupiers? Ask the Irish about that sometime. Norman Davies, in an earlier book on Polish history, quotes a Scotsman as advising the Poles who were recently (re-)subjugated by the Russians: "If you cannot stop the bear from swallowing you, at least do not let it digest you." These are words to live by for all subjugated peoples for preserving their cultures in the face of long-term hostile foreign occupation. And even today, because of arcane British laws, despite the relative sovereignty Wales has regained in the modern U.K., most Welshmen -- who are not Anglicans -- cannot hold many of the highest political offices in the U.K. True, the same is true of all non-Anglicans in the U.K., including in England itself, but a much higher proportion of Welsh are not Anglicans than English. It is a mere detail and a holdover from days when Britain truly was serious about religion, but still, it is an active remnant of one part of a system which denied the Welsh control over their own land.

Now, my purpose here was not to bash the British; I admire Britain -- including the English -- and consider the U.K. one of the sanest countries on the planet. My point was merely to point out however that the historical experiences of the English in relationship to Britain, similar to the experiences of European-derived Americans in their relationship to the United States, is one very qualitatively different from, say, African-Americans, Native Americans...or the Welsh. Though these peoples may now enjoy (finally) the full benefits of citizenship and relative self-government, and are no longer hindered in expressing their culture(s), it is only after a very long history of extreme mistreatment and the current benefits of citizenship notwithstanding, they will never be able to look upon the Union Jack or old Stars and Stripes in quite the same way as a Connecticut-born Yankee with ancestral ties stretching back to the Mayflower. Norman Davies describes this reality in his book by mentioning that for whatever ultimate loyalty the many peoples of Britain may muster for the United Kingdom -- and there is little indication that Wales will attempt to secede any time soon -- any sense of a 'British' patriotism (as opposed to 'English', 'Scottish' or 'Welsh') will not surprisingly often be quite weak outside England (and to a lesser extent, Scotland) itself. Remember that there is no 'British' soccer team; England, Scotland and Wales all have their own teams. How many American flags would you expect to see flying on Lakota Indian reservations in South Dakota this July 4th?

To sum it up, I'll paraphrase an example from an article in Time Magazine from 1992, commemorating the 500th anniversary of Columbus' voyages to the Americas; the article quoted two friends in Brazil, one a descendant of Jewish refugees from the Holocaust, the other the descendant of local Native Indians. Looking out over the ocean, the Jewish Brazilian said, "Columbus' discovery meant salvation for my people," while the (Native) Indian Brazilian responded, "...and it meant disaster for mine."

That's history for ya.

Sunday, April 18, 2010

Tragedy in Poland

The world has witnessed this past week pictures of thousands of Poles congregating in the streets of their cities, heaping flowers and candles on impromptu monuments and weeping uncharacteristically openly in public. The news indeed has been grim, but was President Lech Kaczynski some sort of Jack Kennedy to warrant this nationwide outpouring of grief? Would a similar tragedy involving the Joint Chiefs of Staff bring teary-eyed Americans into the streets?

President Kaczynski was actually a controversial figure in Poland and abroad. Indeed, plans for his entombment in Wawel fortress chapel in Cracow, the historic seat of medieval Poland's royalty, has provoked an outcry from some of his political opponents. So what is behind the huge national reaction to this plane crash?

Most news sources have mentioned the reason for the trip: ceremonies being held at the site of a World War II-era massacre of some 22,000 Polish POWs by their Soviet captors near the modern western Russian city of Smolensk. That earlier tragedy, which took place in 1939-1941 when Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union were allies and accomplices in the 1939 destruction of Poland, is still today an unresolved source of friction between Poland and Russia. Indeed, it played a role in this week's tragedy; Polish prime minister Donald Tusk had agreed to attend a ceremony with Russian prime minister Vladimir Putin last Wednesday, but Polish president Kaczynski had refused to attend that ceremony as the Kremlin still refuses to fully open its archives on the 1940 Katyn massacre to historians. President Kaczynski was on his way to separate commemorative ceremonies at Katyn this past weekend (not attended by Russian officials) when the plane crashed.

But there is much more to this tragedy still. The very ground on which the president's plane crashed is soaked with the blood of Poles and Russians who, in the 16th and 17th centuries, fought one another in countless savage battles for control of Smolensk. But the memories of medieval struggles did not bring Poles into the streets this week; it is the national sense of loss, of having lost again. Medieval Poland enjoyed its successes but modern Poland's history has been somewhat less prosaic, and in 19th century Poland, Russian and German occupiers repeatedly imprisoned, exiled or executed the country's political and cultural elites in a bid to decapitate any resistance and indeed when the country was reborn in 1918, it desperately lacked trained and educated leaders to organize the country. Poland's ruler at the beginning of World War II, Jozef Beck, died in a Romanian internment camp in 1944 after escaping the joint Nazi-Soviet onslaught. The Polish prime minister for the government-in-exile in London during World War II, General Wladyslaw Sikorski, died -- along with his daughter, his chief of staff and several government members -- in a mysterious plane crash off Gibraltar in 1943 at a time when he was strongly opposing Soviet territorial demands, to the open chagrin of both London and Washington. Conspiracy theories about Sikorski's death abound among Poles, and by coincidence, a popular Polish TV network had showed a conspiracy-laden film about Sikorski over the Easter weekend. Sikorski's successor, Stanislaw Mikolajczyk, tried to return to Soviet-occupied Poland after the war to participate in elections but after widespread fraud by the communists and threats from the Soviet NKVD (the 1940s-era KGB), Mikolajczyk had to flee for his life. During the years of Soviet-imposed communist rule in Poland, the government-in-exile continued in London. The last president of the Polish government-in-exile, Ryszard Kaczorowski, resigned his office in December, 1990 after turning over the pre-war seals of office to Lech Walesa, the first freely-elected president of the country since the 1920s. Kaczorowski was among the 96 victims on the plane with President Kaczynski this past weekend.

So while Poles may differ on how they evaluate Kaczynski as a politician, and though all indications at this point are that this was just a tragic accident, his death this weekend has opened old wounds, old wounds in a country all too familiar with tragedy.